Making Art at the End of the World is a monthly newsletter from Los Angeles Print Shop

I used to think that the end of the world was going to be climatic, a giant, fiery climate catastrophe. I’ve now realized that it’ll be like this, a real-time slow melting of everything with so many people acting as if nothing isn’t normal.

And for them that might be true for long enough, but not for all of us. For a long time things have not been good for so much of the world. Have you been feeling it too? The western powers chose barbarism, and so while we continue the fight, we make art.

As artists who run a print shop, Andy and I turn to making art as a survival tool and a form of resistance. It’s how we affirm our existence and make meaning. It’s how we live in unlivable times.

We wanted to start sharing what we’re thinking about and what’s encouraging us every month. We’ll publish an edition of Making Art at the End of the World at the end of every month. We hope it encourages you, too. Most of all, we hope you make art, and then more art.

Have You Been Good to Yourself

The studio air at the print shop has been filled lately with mournful, nostalgic songs, the kind that are uplifting by way of sadness. I’ve often felt hope watching prints come out, and find more of it when listening to Johnnie Frierson.

Johnnie Frierson’s Have You Been Good to Yourself is frank and modest. As he sings the titular line, “Have you been good to yourself?” it seems he’s legitimately concerned about how people are doing, in a way that makes me pause to reflect. When Frierson recorded this song, he was shell-shocked from his time as a draftee in Vietnam and was also grieving the death of his son, and the song shows it. It’s a self-questioning meditation on what it means to be and stay alive in the world we live in from someone really wondering.

“Before the apocalypse, there was the apocalypse of boats.”

The first line of Franny Choi’s poem “The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On.” has been echoing in my brain: “Before the apocalypse, there was the apocalypse of boats”. Easy to think it started recently but it goes back and back and back. Andy and I haven’t always been paying attention to the apocalypses around us — for a long time we were running from fireballs of our own childhoods, building our world around us as we went, the kind of kids who set out with a laptop and not much else (for me it was a stolen one I bought off Craigslist and picked up at an all-you-can-eat Italian place in Queens — have you ever been?). We might be late, but we’re here now.

Escaping to make art

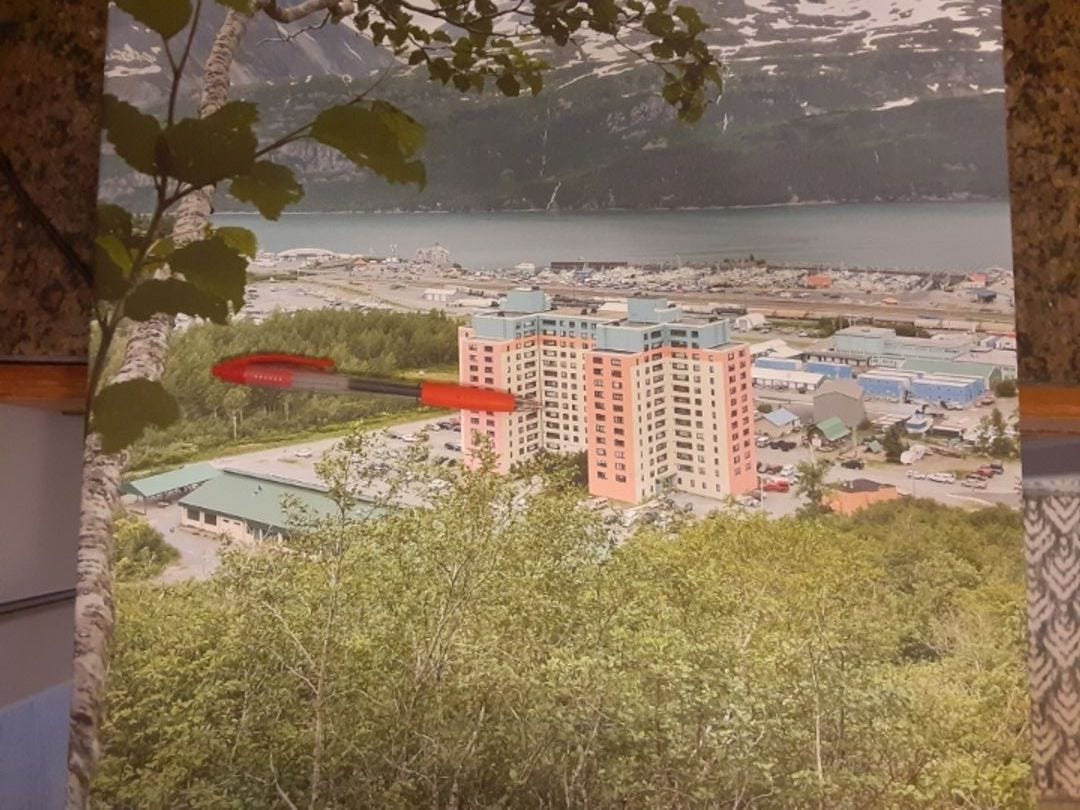

The other night Andy and I were using the self-soothing technique of daydreaming about alternate versions of our own life: What if we lived in a small town, nothing like LA? What if we moved to Alaska? Down the rabbit hole we went to Whittier, Alaska, the town where most everyone lives in the same apartment building. 200 people, 180 of them in one building.

Would it be great, terrible, dangerous, some kind of self-imposed artist retreat, simplifying things so we’re forced to do what we mean to be doing: making more art? A ready-made, built-in community? Would it be the good kind of escape where we leave behind the things that burden us or the bad kind of escape where we pull a geographic and escape towing all the worst things about our life behind us? Or would we just feel trapped and depressed once the one tunnel out of town closed at 10 pm, feeling fine again when it reopened in the morning?

We watched Prisoners of Whittier, a short six-minute documentary introduction to the town. Then we watched Rachel Knoll’s Let the Blonde Sing, a 12-minute documentary about Beverly Sue Waltz, the bartender and karaoke lead at one of the town’s three bars. She was disappointed that she didn’t end up a famous musician, touring the world like she thought she’d be and instead ended up in Whittier while trying to pursue that dream. To us, it seemed like she is certainly doing what she meant to be doing: she’s singing every night for an audience that loves her. We hope we can say the same for ourselves.

Insatiable, we wondered, What else is there out about Whittier? We found this tweet from Adam Morgan — turns out there’s a novel set in Whittier, City Under One Roof by Iris Yamashita, (I’m second in line for the one ebook copy at the library) which we thought was a movie that we could maybe watch right then, but isn’t yet. Thwarted, we went stream-browsing until we found the snowy and dark cover for A Murder at the End of the World, a mysterious, snowed-in escape and also barely related at this point.

It’s four degrees in Whittier right now, there’s a fully-furnished two bedroom for rent until May 31 ($1,400, no pets, decorated with Alaska-themed art). But, people say one person owns half the buildings in the town (thanks, landlords) and a tidal wave once hit the apartment tower. There is so much more to learn and so much to escape to.

Roy

Ambrose Akinmusire’s Roy almost didn’t make the cut. Feels like, “Oh, we’ll just add this little thing here.” It’s one of a few songs on the album that eulogizes jazz trumpeter Roy Hargrove, who had a huge influence on Akinmusire. The song is sad, but uplifting. It’s funereal, disjointed. And the way it ends. My gosh, it just ends there.

Fuck This Shit, Make Art

Here’s a strategy for making art:

Write a list of sentences that charge you up. That acknowledge and give a name to what holds you back from making art today, now. Sentences that when you go back to them you remember the why behind your art. Call it a blessing, call it sentences in list form.

Andy found L'abri Tipton of The Iteration Project who wrote a blessing for their creative spirit in 2024, saying of the project, “I feel ill-equipped to write a blessing. It’s been a long month. I’m emotionally exhausted in ways I haven’t been for a long time. But I also believe such moments might be perfect for practicing the art of blessing.”

We agree.

Here’s a portion of L’abri’s list:

Blessing the Creative Spirit in 2024

May you take time to set up workspaces that inspire you.

May you feel the ennui, then get to work.

Don’t wait for inspiration. Be curious and serious about your own process.

Listen, read, watch, think, converse. Find what feeds you in this season.

May you be brave enough to do diligently what you have to do (a day job?) so you can do diligently what you want to do (probably make art that isn’t super marketable).

May you honour your longing but not drown in it.

May you hold space for thresholds and cross over in big and small ways into the unknown.

Honour the ecosystems supporting your work, even your day jobs, even the strangers.

May you regularly find time to let your mind and heart sink deep into your making and still surface intact enough to move the wet laundry to the dryer, make a grocery list, make a dinner, do a workout, engage in a bit of small talk.

When you need community, may you find those who feed you and avoid those who don’t.

And here are ours:

Esteban:

May you make the art without thinking about its result.

Take a next step, one foot on loose gravel and one already in the air, when you encounter it, no matter how steep it might seem.

May you carve out the space for making art, even if at first it feels small like a beautiful nook whittled out from a spare hunk of wood you had laying around.

Trust your eyes and brain to have rightly mediated and translated the world around you.

Andy:

May you do one thing at a time. May you see this project through one single action at a time. May you feel the joy that your fifteen-year-old self would feel about you making art. May you cook dinner and eat it not alone, and may you have leftovers and may you eat them with your work, and may you have more leftovers, and may you take comfort in knowing one thing in your future is figured out. May you be thankful for this and this and this and even this.

We’d love to know what you write in yours.

Sreo Sam Te

Lastly, Sreo Sam Te by Branko Mataja is a floating sadness. A sadness that’s so big it’s a longing. A sadness with weight to it that you can float in, and maybe even celebrate that you are alive right now with everyone else you know.

P.S. Los Angeles Print Shop makes meticulous large-format (and small-format) prints. It’s always pay what you can for artists and individuals.

If you have a project in mind, let’s make it.

You can start by emailing us, or sending us a DM on Instagram, or making an appointment. We care that you make art and hope that you will.