Would you believe us if we told you we haven’t finished Neptune Frost. We pictured Saul Williams himself walking up to our door to ask us if we’d seen the end of the film. And then us answering, crying, that we hadn’t. So, we watched it. (We typed that before we’d even done it yet, as a manifestation of things to come.)

This video of Saul Williams and Anisia Uzeyman in a closet recommending films they love is basically what we want this newsletter to feel like. Watching them talk makes us want to watch more, makes us hope they make more, makes us want to write and paint and photograph.

So much of the art we saw and printed this month led us back to thinking about the past and what loss and regret and memories make up the past for us. In the show we printed for Katy Shayne, the photos are intimate and revealing by way of location, time, and date. There is a gun on a pillow titled A Portrait. A set of spoons titled Nana’s Coffee Spoons. Are they about spoons, about Nana, about maybe something else unphotographable — the memory of a person? It is clear that together they are markers of moments that hold weight but we never see the thing itself or the non-universal details.

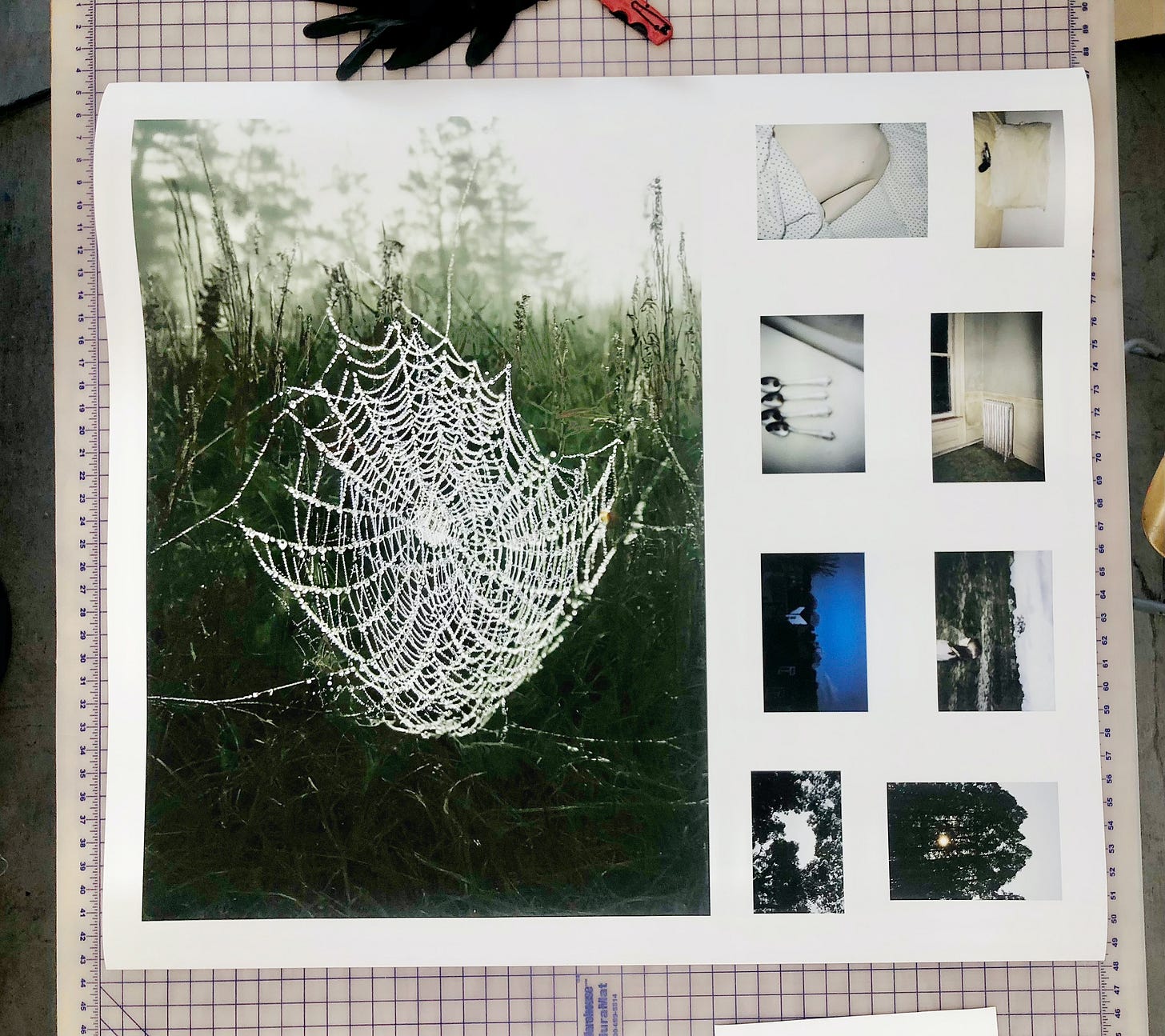

Except for one photo, the biggest one we printed for her show, an AI created dew-y spider web, a “tear laden web”. It shows all the detail — but it is a photograph of something that has “not ever existed.” We will be sitting with this show for a long time.

Artist Lena Rudnick does something similar too. Her photographs we’ve been printing hold deep personal connections to their locations. But at first glance, photography again deceives because the abstract nature of the image draws you in, they are juicy, then the titles tell you this is not just formal but also deeply personal. I wonder if she might feel like the photos say too much (I think they say so much, but that’s not wrong). More to come with Lena’s photographs as we continue making prints for her show next month.

Son Lux at times sounds messy and I remember when I first heard them liking how it felt to hear things overlap in an “un-pretty” way. It was early 2000s and I was young but it still works. It’s not that novel to create art that feels raw and like the demo tape you are listening to might just end, while then also having meticulous constructions of sounds (I actually think that's how they describe themselves in their Spotify bio) — but there it is and when it happens I feel like I have sunken into a deeper rest. I heard this again a few weeks ago and I cannot drop it from my mind. A chorus in a cathedral of everyone singing and playing whatever objects they could find then realizing all of the sounds are as they meant to be and might be fractal numbers converted into a composition.

We printed a panoramic print for Alison Woods, an almost solarized image of tanks on an urban street, that was mounted inside a build up of boxes, dioramas with different scenes. The viewer has to walk up get close and look through the hole to see the photograph. It never pretends to be the real thing, but there you are up close, intimate, wondering what the next portal will show you.

This month we read Dan Leach’s short over on Maudlin House, Self-Portrait at Thirty-Three. The first sentence hurled me in and it’s been a while since I read something that hurled me just right like that. I didn’t mean to be reading it all right then, but after a sentence does that I’m not leaving. I’m staying.

This was the night I lost my job, and you didn’t have a job, and there was a fractious vibe at The Starlight, like someone was about to get killed over something trivial, so I said, Let’s get out of town, and you said, Fuck it, let’s go to Myrtle Beach, and that’s exactly what we did–we fucked it, and we drove four hours to the coast, and we did not die over something trivial at The Starlight.

At first, I thought about how easy it is to escape, Oh just drive to Myrtle Beach, and then I felt the guilt of wanting to escape and the regret of not escaping more often, “See, it would be easy,” just get in the car and point it towards something? Leave at night at a time when we have no obligations? But reading on it's not that simple, an escape doesn't always fix it all (see escaping to Alaska).

One weekend when it was hot out we watched a documentary by Ross McElwee before it expired on lecinemaclub, one hot midday then the other. Ross does escape New York, running away from a break up to document Sherman’s march across the South. In Sherman's March: A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love In the South During an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation, he does document Sherman’s march and also ends up documenting his personal search for companionship across the South.

It was a different look at a potential future, this time from the past looking on at the future that includes now. Will we (the future) be obliterated by nuclear war by now? And even more to the past, what did Sherman's obliteration of the South do to the South today (back then in film time the mid 80s). What is total war and obliteration doing to us today and to the future?

The film is deceptively complex because the art is the thing itself — Ross is not seeking out beautiful landscapes — but there they still are. All these times when we thought we (he) landed in these perfect moments, it’s intermingled with the way his editor self (future) creates it. The edit is almost aggravating. We could feel him go around a feeling or a thought, like he’s passing his arm near our skin but never actually touching us, knowing the whole time that he’s doing that on purpose.

At the end, Andy asked me if Ross got what he came for, by which she meant, did he find a romantic partner? And I said, “Yes, he did. He got his film.” And then, despite knowing that is the full end of the sentence, and part of the wonderful frustration of the whole two hours and thirty-seven minutes, we did look to see if he ever got married. The internet told us the answer, which upon learning, Andy said was not actually her question — her question was the one about art.

At the print shop this month we printed the portrait of a person who is no longer alive. It was not the first time either. Like Barthes said, a photo is always a photo of a will-be-dead person. To look at a photograph of a person is to accept one part of death and dying. To look at and see what is no longer there. This of course assumes that the indexicality of photography does not lie, but it does. (He also said For me the noise of Time is not sad.)

Show Me Love Hundred Waters

Have we told you to listen to this one before? We don’t think so, but aren’t sure. We checked the archives. Still, listen. Or listen again. It’s a minute fifteen seconds of a prayer, a request, a plea, a gently breathy, heartful request.

We hope you’re making art. We hope we get to print some of it soon. If not yours, then whose? Send this to a friend you wish would make more art, or who would watch a movie with you, or who you think of when you think of playing four hours of TV recorded onto a VHS uploaded onto the internet. Would you watch with them wearing headphone splitters or would you plug in the computer speakers, those gray-white ones with the knob?

At Los Angeles Print Shop we make meticulous fine art prints with a pay-what-you-can model — so there’s no gate on these tools for making art. Say hi to get started.

Always a delight to these see pop up in my inbox!